When we built websites we usually started by defining the body text. The body text definition dictates how wide your main column is, the rest used to follow almost by itself. Used to. Until recently, screen resolution was more or less homogeneous. Today we deal with a variety of screen sizes and resolutions. This makes things much more complicated.

When we built websites we usually started by defining the body text. The body text definition dictates how wide your main column is, the rest used to follow almost by itself. Used to. Until recently, screen resolution was more or less homogeneous. Today we deal with a variety of screen sizes and resolutions. This makes things much more complicated.

In the heat of relaunching ia.net I wrote a quick weblog post on responsive typography, focusing solely on the aspect of our latest experiment: responsive typefaces. Without knowing the history of iA, you’d miss some key aspects to the responsive typography and design in our relaunched site. I decided to start from scratch and explain responsive typography in detail, step by step. This is step one.

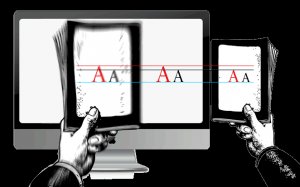

To avoid designing different layouts for every possible screen size, many web designers have adopted the concept of Responsive Web Design. In a nutshell this is the idea that your layout automatically adapts to the device viewport. There are different ways to do it, but I like to put it this way:

- Adaptive layouts: adjusting the layout in steps to a limited number of sizes

- Liquid layouts: adjusting the layout continuously to every possible width

While both have advantages and disadvantages, we believe that adaptive with as few break points as possible is better, because readability is more important than having a layout that is always as wide as the viewport. This is a debatable opinion on a complex matter in itself, but optimal readability requires a certain amount of control over the measure (column width) of the text, and in this regard a liquid layout creates more problems than it solves. More about that another time.

While both have advantages and disadvantages, we believe that adaptive with as few break points as possible is better, because readability is more important than having a layout that is always as wide as the viewport. This is a debatable opinion on a complex matter in itself, but optimal readability requires a certain amount of control over the measure (column width) of the text, and in this regard a liquid layout creates more problems than it solves. More about that another time.

Note: Responsive design already incorporates a lot of macro-typographic issues (type size, line height, column widths), so responsive design already incorporates responsive typography in many ways. What we focused on in our responsive typography article mainly referred to our use of graded fonts on ia.net. I’d like to talk about grading in the next post and dive right into the basics of responsive macro typography on the screen now.

The Right Tone

Sooner or later, you need to decide what kind of typeface to use. The choice of your font is mainly a matter of tone, but as every typeface has its own qualities, and demands (or forbids) certain treatments, the choice of type has a lot of visual and technological consequences. With web fonts you now have a big choice of typefaces, so finding the one that fits has become yet another challenge.

In 2012 we designed our own typeface iABC for this website to experiment with responsive typography. We chose a serif because it fits our tone, and mirrored the refinement of our content (or at least that’s what we thought). For iA Writer we chose a monospace typeface. Because the primary purpose of our program is helping you getting a first draft out, we specifically chose Nitti—a typeface that feels strong and careful at the same time. The decision to use a monospace typeface also came about because the first iPad’s Operating System didn’t auto-kern proportional typefaces. Instead of using a proportional typeface that would be rendered poorly, we decided to go for a monospace typeface right away.

In 2012 we designed our own typeface iABC for this website to experiment with responsive typography. We chose a serif because it fits our tone, and mirrored the refinement of our content (or at least that’s what we thought). For iA Writer we chose a monospace typeface. Because the primary purpose of our program is helping you getting a first draft out, we specifically chose Nitti—a typeface that feels strong and careful at the same time. The decision to use a monospace typeface also came about because the first iPad’s Operating System didn’t auto-kern proportional typefaces. Instead of using a proportional typeface that would be rendered poorly, we decided to go for a monospace typeface right away.

Three years later, our love for Nitti has led to the custom proportional (and graded) version you’re reading now.

Serif or Sans Serif?

Serif or Sans Serif?

Usually the choice falls between serif and sans serif. This is in itself a complex matter, but there is a simple rule of thumb that might help you: The serifed typeface is a priest, the sans is a hacker. One is not better than the other, but, for various reasons, a serifed typeface has a more authoritarian touch, whereas a sans serif feels more democratic. Remember, this is five thousand years of typographic history wrapped in two sloppy lines—don’t take it too seriously.

A lot of people still think that for screen typography the question “serif or sans serif” answers itself. Actually, it’s not that easy. Against common beliefs, both serif and sans serif can perform equally well, if you choose a body text size above 12 pixels. Below 12 pixels serifed typefaces don’t render sharply enough, but (and this brings us to the second point) on contemporary monitors 12 pixels is definitely too small anyway.

What Size?

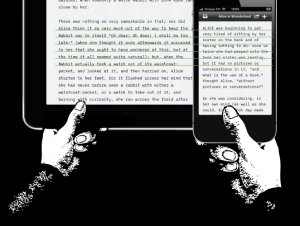

The size of your body text doesn’t depend on your personal preference. It depends on reading distance. Since computers are generally further away than books, the metric size of a desktop typeface needs to be bigger than the sizes used for printed matter.

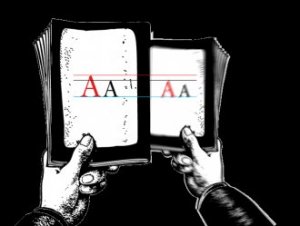

The illustration below shows that the further away your body text, the bigger it needs to be. The two black and the two red A’s have the same metric size. But since the right pair is held further away, the perceived size is smaller. The red A in the right image has the same perceived size as the black A in the left image:

The further away you hold the text, the smaller it becomes visually. You need to make the text size bigger the further away the text is read, to compensate for a larger reading distance. How big is, again, a science in itself. If you are inexperienced, a useful trick is to hold a well-printed book at a comfortable reading distance while looking at your website to compare.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE