Responsive design, which allows designers and developers to build websites that adapt to every screen size, is one of the most empowering web tools to be adopted in the last decade.

Responsive design, which allows designers and developers to build websites that adapt to every screen size, is one of the most empowering web tools to be adopted in the last decade.

Responsive philosophy is not just about designing websites that adapt to screen size.

But adapting to the screen is only the first frontier of a new, responsive web. Today, users expect online experiences that not only respond to what device they're using, but also their location, time of day, what they’ve already read, and events happening in real time.

To capture a user’s attention for the next generation of the web, you’ll need more than just responsive design. You’ll need a responsive philosophy.

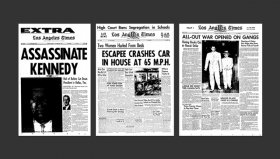

When you look at the print version of any major print publication over time, you realize that they don’t just have a couple of templates. They have hundreds. They have the ability to respond to any combination of events with a design that gives each event the proper editorial weight.

Somehow, we’ve lost that ability on the web. Most homepages use the exact same layout, day in and day out. And it’s not just homepages. Article pages—where most users first land on websites—look exactly the same, too. To a user, a day when war breaks out in Iraq can feel exactly the same as a day when the biggest news is a change in Bieber's hairstyle.

These limitations aren’t just stifling for readers. The lack of variation in online presentation limits a news organization’s ability to communicate its perspective and editorial voice to readers through design choices.

These limitations aren’t just stifling for readers. The lack of variation in online presentation limits a news organization’s ability to communicate its perspective and editorial voice to readers through design choices.

It’s no wonder that some publications feel so one-dimensional online: not all are equipped respond to events with the cultural understanding and editorial vision that once made newspapers so essential.

Websites should do more than respond to devices. Web experiences should respond to multiple contexts so that they’re meaningful to every reader, in every moment, on every device.

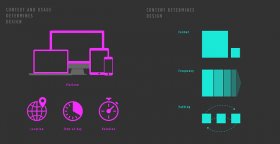

One example of this approach is the reuse of elements. We’ve long noticed that publishers invest massive amounts of energy and resources designing front-page and section treatments, and spend too little time designing elements for the articles themselves. An easy way around this is to empower editors to reuse packages of content originally designed for one context anywhere on the site, and make these packages automatically respond to their context.

For example: on the homepage, a gallery might expand to take over the entire width of the page. On an article page, it might take up only half the page. This allows editors and designers to create unique designs quickly without repeating work they’ve already done.

The other place where a responsive philosophy can figure prominently is at the bottom of an article page. Unlike the print newspapers of yesterday where the front page sold the newspaper, most visitors to today’s news websites visit to read a particular article. They may never visit the homepage. To convert them into multi-page and even repeat visitors, you have to capture their attention as soon as they finish the article and direct them on the path most likely to make them stick around.

To convert them into multi-page and even repeat visitors, you have to capture their attention as soon as they finish the article and direct them on the path most likely to make them stick around.

To address this, most publishing sites throw in a comments section or put a static, poorly designed "recommended content" module at the bottom of the page. What they should be doing is reusing more dynamic designs and responding to users to create an ideal path for them to follow.

As brands become more publisher-like, they’ll need to incorporate a responsive philosophy.

When users finish an article, why not allow them to continuously scroll right back into the section page? The section page is already well-designed and editorially curated to contextualize the article in a larger flow of news. Scrolling back into it after an article feels completely natural, and invites the reader to dive deeper into the section.

From there, you can incorporate what you know about users. It's easy to glean what device users are browsing on, the time of day they’re visiting, where they are in the world, whether they’re regular or new visitors, how long they’ve been on the site, and where they’ve just come from.

When we redesigned the Los Angeles Times, we collaborated with the Times on an algorithm that automatically decides the best thing to serve each user, based on all the information we know about them. Crucially, the system still allows editors to override those choices when they need to respond to major events.

For example, if users come in through an article on the Times' Dodger’s blog, and they’re frequent readers of baseball articles, the default setting might be to serve them more sports content. But if an earthquake has just happened, an editor can override that behavior to serve the news organization’s editorial agenda.

As this philosophy becomes more commonplace, you can imagine a new role developing inside newsrooms. This person would combine a deep understanding of the editorial mission with empathy for the user to constantly tweak the algorithms governing how readers consume content, and design responsive pathways throughout the site that keep users engaged.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE